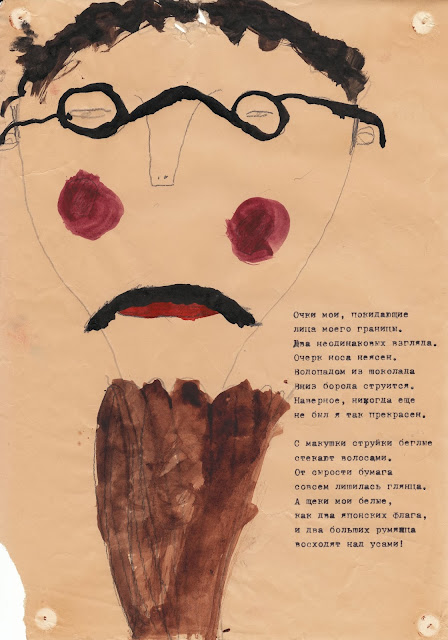

Poet

- A.A.

Being a poet is pleasant, very nice,

even with lungs that nicotine has blackened.

The rest all toil away while he, the blackguard,

is lapping up the milk of paradise.

Deceit for dopes, that ‘agony of words’,

a formula for staying out of prison.

Freedom it is—no worries and no mission—

to catch those words and set them down in verse.

Poets feel free to chirrup in their notes,

like a mother sow feeling she’s going to farrow.

And which of them dies early? It’s the fellow

who finds it work. He’s really writing prose.

(Translation © G.S. Smith)

Поэт

- А.А.

Поэтом быть приятно и легко,

пусть легкие черны от никотина.

Пока все трудятся, поэт, скотина,

небесное лакает молоко.

Все “муки слова” — ложь для простаков,

чтоб избежать в милицию привода.

Бездельная, беспечная свобода —

ловленье слов, писание стихов.

Поэт чирикать в книжках записных

готов, как свиноматка к опоросу.

А умирают рано те из них,

кто знает труд и втайне пишет прозу.