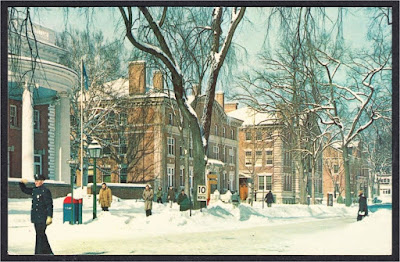

A Postcard from New England, 1

To Joseph

The students are heading down to their waterhole, bawling and butting,

five o’clock has danced out from the library’s neck-worn sleigh bell,

and, striking up something of yours—you’ll have noticed—a neat little motive,

I head down to my tumbril.

I loosen my collar, my belt, and my thinking in English,

as my dischargees disperse, a bunch of disgruntled fighters.

Fearful of water (again he’s not bothered to wash!) poor Evgenii’s

got a bit of a limp in his stress-bearing foot, tetrameteritis.

Rodión’s splitting sticks in an ancient lady professor’s back garden,

(they’re all going over to wood-stoves these days, for the times get nastier),

and though he’s corroded (and how), my Kholstomér tried his hardest

to manage a gallop. A final neigh, and he’s sent to night pasture.

I see shepherds, the old and the young, starting up their campfire,

lighting substantive kindling from a verb that is only singular,

and I’m made heavy-hearted, my vision diluted with damp, by

Gorchakov’s hunchbacked shade as it creeps down the hillside.

This, then, is the way that we live, this the way our days are devolving,

Italian tutors we, Karl Ivanyches, Pnins, the crippled.

Such are our works and our days. And such the loaves that

we bake. But our colleagues are different.

Heraclitus (remember he’s ‘Doctor’!) is really a big boy for blether —

his showy jog down by the river shows him up for what he

is, a coward, poor dear; in Adidas sneakers — skirting round depth, he

would so like to dip them again in the very same water.

As for us, in our bloodstream we’ve built up enough stearin for

candles to see us through February nights, the longest.

Trochee-crazed Rodiónovna, like in our needy youth, Arina,

still has that crock of rotgut, now in her needy dotage.

I have raised up a monument, perch for this feeble turtle

dove. ‘There’s drink left, I hope?’ She responds, ‘Most assuredly, mister’.

Joseph, adieu. My friend, if you get through your meat-grinder battle,

and you happen to be in these parts, be sure to pay us a visit.

L.

PS

Mrs General Drozdóv does improve. Less swelling now in her legs

(like treetrunks they were, you remember).

And Varvára Petrovna’s in heaven —

son back from his Switzerlands.

L.

(Translation © 2019 G.S. Smith)

From Чудесный десант (The Miraculous Raid), 1985

Translator’s note: I would like to thank Barry Scherr for expert advice on this translation.

‘Something of yours’: Loseff has in mind the metre of this poem: not classical hexameter, but the rhymed long-line free dol′nik with variable anacrusis of the type that Joseph Brodsky developed and used extensively in his poetry after his emigration in 1972. An example of this metre with the same stanza form (ABAB quatrains) as ‘A Postcard’ is the first segment of ‘Новый Жюль Верн’, which is dedicated to Lev and Nina Loseff: ‘Безупречная линия горизонта, без какого-либо изъяна./Корвет разрезает волны профилем Франца Листа./Поскрипывают канаты. Голая обезьяна/с криком выскакивает из кабины натуралиста.’

Throughout this poem, Loseff refers to people (except for Heraclitus) using the names of well-known characters from canonical Russian literature.

Evgenii is the hero of Pushkin’s The Bronze Horseman, whose life is ruined as a result of the catastrophic Petersburg flood of 1824.

Rodión Raskol′nikov is the hero of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

‘I see shepherds…’: The subtext here would appear to be the sixth stanza of Brodsky’s ‘24 декабря 1971 года’: ‘То и празднуют нынче везде,/что Его приближенье, сдвигая/все столы. Но потребность в звезде/пусть еще, но уж воля благая/в человеках видна издали,/и костры пастухи разожгли.’ Pushkin’s ‘Prophet’ perhaps forms the subtext of the second line.

Kholstomér is the clapped-out gelding who narrates Tolstoy’s story to which he gives his name; the value of his honest life of toil outweighs that of the humans who have abused him.

In Joseph Brodsky’s ‘dialogue in the madhouse’ ‘Gorbunov and Gorchakov’ (1970), the two characters named in the title are usually regarded as alter egos. Gorbunov is referred to in Loseff’s poem by an adjective derived from the word his name evokes, gorbun,‘hunchback’, rather than his proper surname.

‘Italian tutors’: Baratynsky wrote a famous elegy (1844) on his childhood live-in mentor, the Neopolitan émigré Giacinto Borgese. The German émigré ‘Karl Ivanych’ was the tutor in the Tolstoy household, and is portrayed in ‘Childhood’; see also Loseff’s ‘Poem about Novel, 2’, posted here on 30 March 2016. Timofei Pnin, the pitiable Russian émigré who teaches in an American college, is the hero of Nabokov’s novel of that name (1957).

Arina Rodionovna was Pushkin’s sister’s nurse. The immediate subtext here is Pushkin’s

poem ‘Winter Evening’, which uses trochees to evoke Russian folk poetry. Tired out, Arina Rodionovna dozes by the fire, and Pushkin invites her (‘old woman of mine’) to take a drink with him ‘out of sadness’, calling for a bowl (kruzhka, as in Loseff).

‘I have raised up a monument’ echoes the opening line of another of Pushkin’s best-known lyrics, ‘Exegi monumentum’, based on Horace’s ode.

‘get through your meat-grinder battle’: Joseph Brodsky had his first open-heart surgery in 1979, and later two bypass operations.

Praskov′ya Ivanovna Drozdóva, a rich landowner, widow of General Tushin and mother of Nikolai Stavrogin’s mistress Liza Tushina, appears in Dostoevsky’s The Devils; she does indeed suffer from peripheral edema. The imperious and scheming Varvára Petrovna Stavrogina, her ‘friend’ since schooldays, is the widow of General Stavrogin, mother of Nikolai Stavrogin, and protector of the sinister Stepan Verkhovensky.

Открытка из Новой Англии. 1

Иосифу

Студенты, мыча и бодаясь, спускаются к водопою,

отплясал пять часов бубенчик на шее библиотеки,

напевая, как видишь, мотивчик, сочиненный тобою,

я спускаюсь к своей телеге.

Распускаю ворот, ремень, английские мысли,

разбредаются мои инвалиды недружным скопом.

Водобоязненный бедный Евгений (опять не умылся!)

припадает на ударную ногу, страдая четырехстопьем.

Родион во дворе у старухи-профессорши колет дровишки

(нынче время такое, что все переходят опять на печное),

и порядком оржавевший мой Холстомер, норовивший

перейти на галоп, оторжал и отправлен в ночное.

Вижу, старый да малый, пастухи костерок разжигают,

существительный хворост с одного возжигают глагола,

и томит мое сердце и взгляд разжижает,

оползая с холмов, горбуновая тень Горчакова.

Таково мы живем, таково наши дни коротая,

итальянские дядьки, Карл Иванычи, Пнины, калеки.

Таковы наши дни и труды. Таковы караваи

мы печем. То ли дело коллеги.

Вдоль реки Гераклит Ph. D. выдает брандылясы,

и трусца выдает, и трусца выдает бедолагу,

как он трусит, сердечный, как охота ему адидасы,

обогнавши поток, еще раз окунуть в ту же влагу.

А у нас накопилось довольно в крови стеарина —

понаделать свечeй на февральскую ночку бы сталось.

От хорея зверея, бедной юности нашей Арина

с то же кружкой сивушною, Родионовна, бедная старость.

Я воздвиг монумент как насест этой дряхлой голубке.

— Что, осталось вина? И она отвечает: — Вестимо-с.

До свиданья, Иосиф. Если вырвешься из мясорубки,

будешь в наших краях, обязательно навести нас.

Л.

P.S.

Генеральша Дроздова здорова. Даже спала опухоль с ног

(а то, помнишь, были как бревна).

И в восторге Варвара Петровна —

из Швейцарий вернулся сынок.

Л.